The Newsroom

Excerpt: Kim Dorland – Introduction

Introduction

Going Out on a Limb

Is art damaged? Is painting irreparably harmed? When you read the published preambles to the discussions of Kim Dorland’s art, you might very well get the impression that we accept that painting is a goner. Kim Dorland didn’t get the memo.

Dorland makes exquisitely ugly paintings. Achingly poignant, touching, melancholic but ever so vital, his work is a study in contradictions and contrasts: beauty and defilement, exhilaration and denouement, elegance and the tawdry, happiness and despondency. He is fanatically dedicated, making an astonishing number of works in a variety of media and scales. He ransacks art history, exploring almost every theme and subject. And he is tireless in his pursuit of pushing the limits of his own taste. Someone forgot to tell him that it is all over, finished. Thankfully.

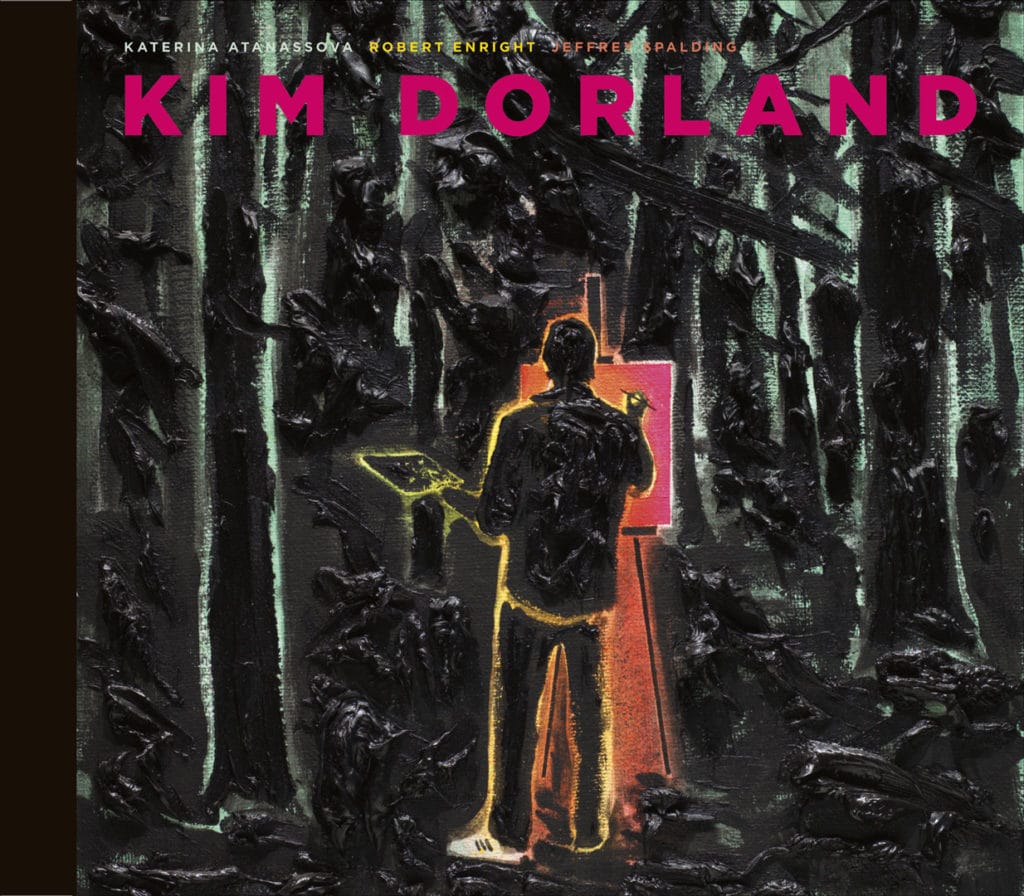

Recently, the artist concluded a residency with the McMichael Canadian Art Collection that resulted in an exhibition pitting his work alongside Group of Seven works from its collection. Clearly, it was a triumph, with the exuberant Dorland works of grand scale playing off against the intimate sketches of the Group: Hot Mush School 2014. Harris, Thomson, and Milne were all “quoted” by his responses. Tellingly, Dorland responded to the post-impressionistic work of the Group—that is, the Group’s style before its dramatic stylistic turnaround in 1921 in response to “the call to order.” Dorland’s lush impasto excesses result in works of great power; many of these could be termed true homages to this legacy. In this respect, these works in combination with his Emma Lake pictures provide an adoring embrace, a sweeping emotional endorsement of the power of art to move us and uplift our spirit. His paintings that capture the artist, easel, and painting set amidst the trees are so touching—a closing of the circle, an extraordinary gesture of respect from one generation to another. They are powerful, iconic, and so convincing that it is possible to cast these as prototypical, signature-style Dorland works.

Yet they careen us off the centre of where Dorland lives. He doesn’t seem to believe in the redemptive power of nature, the theosophical underpinning of the Group’s commitment. Perhaps Dorland sees nature, life, or spirit as damaged? Kim Dorland’s art is inhabited by ghosts. Many of his works wrestle with the demons of his past life, reflections upon uncomfortable, bumpy teen years and early manhood spent in Alberta. Kicked out of the house as a teenager, estranged from his parents, without home or emotional rudder, he was saved by art and Lori Seymour. Seemingly, he wishes to repay the debt by saving art through countless painterly tributes to his muse—his spouse, Lori—as well as to his children.

In the mid-1950s, Graham Coughtry would speak for the aspirations of the art of a new generation by infamously exclaiming that “every damn tree in the country has been painted.” Working today, Kim Dorland’s art observes that “every damn tree in the country has been painted upon.” It may still be plausible to manufacture an encounter with pristine wilderness, but it is not our predominant, day-to-day lived reality. Instead, we learn to endure urban gardens strewn with debris and dog feces, buildings and trees “tagged” by graffiti artists, posters, and advertisements.

Great city “green spaces” are also the scene for many indecent, lewd acts. Much of Dorland’s art visits this aspect of nature. A nearby forest retreat is not an oasis and source of spiritual release but a place for the disenfranchised to come together, inhabit, and somewhat own—a teenage universe. His bush party paintings remember his high-school years in Alberta, drinking, fighting, or one’s “first time” in the backseat of an old beater or under a railway bridge. In so many ways, the sentiments captured by these paintings are painful, despondent, and so very dreadful. Yet they are real. They reflect the lived experience of legions of youth: cue Kurt Cobain, and Isabella Rossellini in the movie Blue Velvet. So perhaps we must smile and accept. Dorland’s paintings move me.

Kim Dorland has been exceedingly forthcoming and generous in his expression of admiration for and emulation of several powerful artistic influences. A certain number of them are recounted in every published account, so I won’t recite herein. To be honest, it is probably because I don’t actually feel these “grand” references are all that pertinent to a discussion of his work. Instead, I perhaps take a different view. I wonder whether much of Dorland’s temperament was honed in the west, in Alberta?

Whereas much of the twentieth-century art of eastern Canada might have been about beauty and extraordinary views, art in western Canada tended to be far more prosaic, understated, pedestrian. Dorothy Knowles, A.C. Leighton, Walter Phillips, Jim Nicoll, and so many more made paintings of vernacular, down-to-earth, everyday reality. Wilf Perreault has made a career out of painting muddy backstreet residential alleyways; David Thauberger has chronicled the wartime suburban houses of his hometown; photographer Danny Singer looks at main street small-town Alberta. Dorland’s “portraits” of trailers, trampolines, teens, and suburban houses reside within this tradition. All choose to record the ordinary, the mundane, in preference to the exemplary. Dorland adds further pathos—empty beer cans, starving dogs, dilapidated cars, spray-bombed fences, strip-mall convenience stores, trailer park boys—diminishing expectations. Why am I not totally depressed by these works? Do I even like, never mind love, these paintings? I suppose I do, because they strive to tell the truth. Dorland’s art declares: This is our reality; this is what we have come to.

Kim Dorland’s figuration and landscapes sit as a continuity of Canadian art history, not as an anomaly. Institutional authority may undervalue the likes of Joanne Tod, Paterson Ewen, W.L. Stevenson, Maxwell Bates, Michael Smith, Landon Mackenzie, Arthur Lismer, Goodridge Roberts, John Hartman, Doug Kirton, Harold Klunder, William Ronald, Claude Breeze, Jean-Paul Riopelle. Should we mention Karel Appel and CoBrA? I can assure you, given Dorland’s voracious interest in art, he does not. His work is so evidently mindful of the glories of other beloved art.

Kim Dorland has created some of the most aggressive, awful paintings. Their malaise hurts; some make me very sad. He has “tagged” art history: I’m awfully glad.

Taken from Kim Dorland – available now.