The Newsroom

Excerpt: “Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun”

The following is an edited version of the Preface by Larry Grant taken from Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Unceded Territories by Karen Duffek & Tania Willard.

I understand the conflict that Lawrence Paul’s paintings are about. And it’s not an imaginary thing—it’s real. It’s the reality of Canadian history and the way Canadian society and others have used and subjugated the Aboriginal people of this land, wherever they’ve gone to get resources. To me, that’s what’s crying out in his work. It’s an outcry about the injustices perpetrated by Canadian society on Aboriginal people—and they’ve done such a good job of it that many people are not able to accept or understand that this has actually happened in Canada. I think that’s part of the agony that comes out: knowing that we live in unceded lands occupied by Canada and controlled by Canada through different acts of legislation, which persists to the present.

Lawrence is an Aboriginal person who grew up on Aboriginal territory and moved to the Greater Vancouver area—Coast Salish territory, but away from his father’s and mother’s reserve communities, his roots. Being who you are can pull you back to the territory of your familial roots, but living in an urban area, it’s like the anonymous society of the Western world. You can be who you want to be if you’re not within the community of your ancestors. That, I think, gives you the academic and artistic freedom, whether it’s with paintings or with words, to come forward with something that is directed to contemporary society and helps people to understand the injustices of the past and present. And it’s not just to be anonymous: it’s to be out there, to have a voice without having to be labelled as being from this community or that community. You’re an Aboriginal person of Canada on unceded lands.

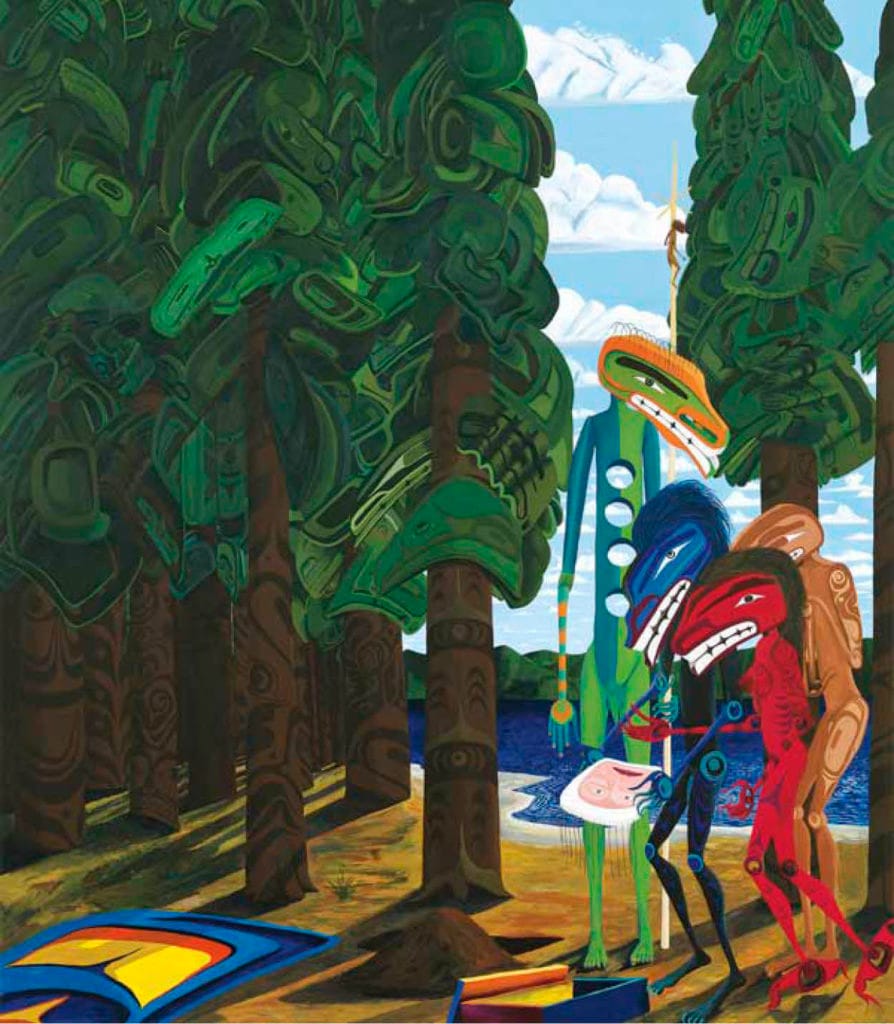

As Salish people we would have traditionally been able to move all throughout Salish territory with freedom and not be restricted. The only restrictions we would have had were our cultural teachings—but I feel that the teachings really give you an anchor that your mind needs. In my experience as an adult learning to analyze our Musqueam h?n?q??min??m? language, there’s nothing else that I’m aware of that gives you an identity the way language does. It ties you to an area, it ties you to geography, to the flora and fauna, and to the cultural aspects and the spiritual aspects of your life. I see and hear in Lawrence’s work that he does not want to be restricted to his own cultural mores, ones that many Salish artists today have gone back to—Coast Salish artists using Coast Salish forms, closely resembling the old-style work. Instead he brings his artistic skills and his artistic interpretation to representing the acts of oppression, the acts of subjugation, the conflicts that have happened and are still happening today to our people, and probably to all the Indigenous peoples of the world. He’s using cultural and artistic license to create the visions that he has: the stories, the message, the way he incorporates Western figures with Aboriginal figures. In a sense the Aboriginal figures in his paintings are anonymous because they’re not Coast Salish in style. I see them wearing masks that I don’t believe are part of his Salish background: they’re Nuu-chah-nulth style, or from up north. But he’s saying, “I am an artist and I have artistic licence, and I will do it in this form to tell my story.” He’s being a frontline activist, trying to throw off the chains of cultural restraint, taking us out of the ancient terminology into contemporary terminology, but still showing the arguments that we have between colonization and who we are as a people.

I think we’re on the same path, he and I, but we’re using different approaches. Lawrence is making a statement very much like what I’m doing when I speak at the Museum of Anthropology and other places and welcome people to the unceded lands of the Musqueam people. We are addressing the question of how you destroy a people, without killing them physically, to access the resources of the land they’re on. To use the words of a movie that our little grandson loves, “We become minions of the state.” We become subjugated people who have no background. We don’t know who we are because of that—and in Lawrence’s art, he’s trying to say that. He tells stories that are contemporary in the sense of depicting the oil companies, the logging companies, and how our ecology is being desecrated. They’re about the Indian Act and all the legislation that brings us the lack of identity, the loss of community, the loss of language, and the belief that we as human beings must control everything that’s there before us without allowing it to move in its own natural rhythm.

We have to want to make a better world for our future generations. They need something that’s better, and we need something to affirm who we are so that we, as Indigenous people, have a culture, a complex language system, and our own identity—all that Canada has done its best to not acknowledge.

Aboriginal people have been talking about this ever since we can remember, but now there’s a broader realization: “Wait a minute. We’re all connected. If that oil spill messes up our beach, what are we going to do?” It’s about us, here, trying to save Burrard Inlet, False Creek, the Fraser River. It’s an ancient story that comes from the background of Aboriginal people who, I think, are finding their way to be heard and to be understood within contemporary society. Whether it’s through paintings, carvings, stories, or oral presentations, this is what it’s about—not “it’s your fault and not my fault,” but “we’ve got to make it better.”

Now we have allies who are aware, and who are adding their voices to our calls for change. It all comes through being persistent and persevering in our story, and not wavering from the actual argument. And at the heart of this movement, this resurgence, Lawrence Paul’s art cries out really loud—and really, really clear.

The full-colour publication, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Unceded Territories, featuring essays by local and international writers and illustrated with selected works by Yuxweluptun, accompanies the exhibition currently on display at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC.