The Newsroom

Author Q&A: Enemy Alien

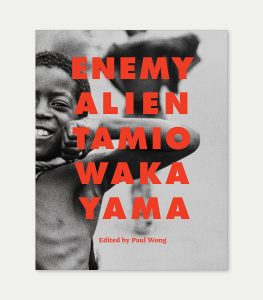

Paul Wong is an award-winning artist and independent curator known for pioneering early visual and media art in Canada. He is the editor of Enemy Alien: Tamio Wakayama (September 2025, Figure 1) and the curator of a major solo exhibition and retrospective of works by Wakayama at the Vancouver Art Gallery, which runs until February 2026. Paul Wong joined Figure 1 to discuss Wakayama’s life, work and legacy.

F1: Tamio Wakayama’s early life was marked by his family’s internment in Canada during the Second World War, and he described his boyhood years as “a kaleidoscope of joy and pain,” largely due to the racism he and his family faced. How do you see those early experiences of injustice and cruelty shaping the way he later approached photography and activism?

PW: Tamio grew up branded as an “enemy alien.” Not just him, but the 22,000 other Japanese Canadians who were forcibly removed from their homes. To grow up under that kind of discriminatory, oppressive label—it’s unimaginable. His family was exiled to Chatham, Ontario, forced to start all over again. As a child, that’s just the world you know. You learn to live with that hate and repression, to negotiate it while trying to find your place in the outside world. So he grew up living in two halves—one inside the family, where there was love and survival, and one outside, where he had to face racism and exclusion every day. That sense of division, of never being whole, really shaped him—his view of the world, his art, his activism.

In his memoir, Tamio talks about how his father had to rebuild from nothing. Before the war, he’d built a successful small business in rural Vancouver, but after the internment, he ended up working in a slaughterhouse. Imagine that—losing everything, then having to start again doing brutal work just to support your family. And then, tragically, his father was killed—hit by a drunk driver walking home from work. Tamio mentions it only briefly, but you can feel the weight of it.

That’s the human tragedy of it all. This is what happens when people are displaced, when everything they’ve built is taken away. Growing up with that kind of loss at home, and with sanctioned racism outside—it’s devastating. But it’s also what gave Tamio his deep empathy, his understanding of injustice. It’s what shaped his eye as a photographer and his voice as an activist.

F1: Wakayama’s 1963 decision to drive to Birmingham after the church bombing that killed four little girls was both spontaneous and transformative. What do you think compelled him to step so fully into the civil rights movement at that moment?

PW: The early 1960s were a time of huge social change. The civil rights movement was gaining momentum. You could see it happening live on television—the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech. But it was John Lewis, who was then head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who really inspired Tamio. He was so affected by Lewis’ position on the social revolution and what was happening in the South that, within weeks, he packed up his Volkswagen Bug and drove down there. He felt compelled—it wasn’t something he planned as a big gesture, it was just something he had to do before returning to university. (He never returned to University ) And once he got there, he found his place. He started volunteering with SNCC, and before long he was on staff, fully embedded in the movement.

F1: Wakayama’s activism and photography extended beyond the United States, later focusing on Indigenous and Doukhobor communities in Canada. How did his experiences with internment and the civil rights movement influence his commitment to documenting these groups?

PW: When Tamio left for the U.S., he went as “Tom.” While there he learned how to be a photographer and returned home as Tamio, and he continued to be involved in anti-racist, anti-war activism in Canada. When he was given the opportunity to document Indigenous and Doukhobor life, to be welcomed into those communities that were marginalized and disenfranchised, he was grateful for the chance. He identified with them as a result of the oppression his own family and the Japanese community faced in Canada.

F1: Enemy Alien includes archival material—contact sheets, newspaper clippings, and letters—that provide context for Wakayama’s images and memoir. What do these materials add to the reader’s understanding of his journey?

PW: You know, up until 1963, when Tamio began taking his own photographs, we really had nothing visual from his early life. So it felt important to include family photos, government archives, newspaper clippings, and letters to help fill in that history, to show what he came out of. There’s one page in the book with three different identity cards—each a different colour—representing Japanese-National, Canadian-born, and Naturized Canadian. Every Japanese Canadian had to carry these ID cards,. I wanted to show those, along with the official notices the community received every day—rules about curfews, turning in cameras, packing a suitcase, relocating instructions.

Looking through all that material, you realize how systematic this oppression was. It wasn’t random or gradual—it was an onslaught. Daily and weekly orders stripping people of their rights, their homes, their dignity. They were told, “Pack one suitcase. Your property will be looked after.” But of course, it wasn’t. Everything was sold off immediately. Those documents make visible the machinery of displacement and injustice that shaped Tamio’s life—and the world he eventually chose to confront through his photography.

F1: Looking at Wakayama’s legacy today, why do you think his life and work remain urgently relevant to contemporary conversations about racial justice, solidarity, and community resilience?

PW: The title Enemy Alien isn’t something we made up—that was the official label stamped on Japanese Canadians. That’s how they were identified. And now, when you look south of the border, you see the same language and laws—the Alien Enemy Act—being used to round up and deport migrants, both documented and undocumented. This exhibition and book remind us how history repeats itself. The rights and equity we think we’ve secured can be lost again so easily. I think that’s what you take away from Tamio Wakayama’s life and work—his unflinching commitment to documenting injustice and holding society accountable.

Order your copy of Enemy Alien now.