October 9, 2025

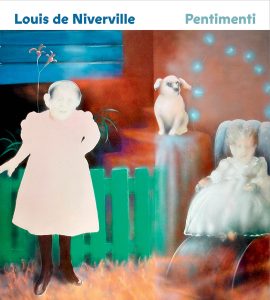

Author Q&A: Louis de Niverville: Pentimenti

Throughout his illustrious career, Louis de Niverville drew from his childhood trauma to create experimental and thought-provoking art. The co-editors of Louis de Niverville: Pentimenti, Thomas Miller (de Niverville’s partner of many decades) and international art dealer Philip Ottenbrite, joined Figure 1 to reflect on this tribute to the artist’s life and work.

Louis de Niverville

Figure 1: Louis, born the ninth of thirteen children, spent four years of his early childhood in a tuberculosis sanatorium. How do you see those years—marked by illness, isolation, and imagination—reappearing in his work?

Philip Ottenbrite: The years spent in isolation were important in terms of the basic craftsmanship Louis honed and depended on to fill his empty days and for enhancing his imagination. So many of the comic book images he cut out from the newspaper showed up in his work throughout his career. While hospitalized he was not taught to read and write to his visual vocabulary developed beyond that of most children.

Thomas Miller: Louis’ work explored the closeness and safety of the family from whom he was separated in the hospital years. The theme of isolation was central to his two large public commissions: the mural for Sick Kids Hospital, and the Spadina Subway mural.

F1: It has been suggested that Louis was a Surrealist, but he did not consider himself to be one. Why did he wish to disassociate himself and his art from that movement, and do you think it’s fair to call him a Surrealist when he didn’t identify as such?

PO: Surrealism is a term often thrown around to describe anything dreamlike but it has a real definition when applied to the movement around 1920. Surrealism describes images created by the subconscious while we sleep. Louis’ work was created by daydreaming when he was in complete control of his imagination.

TM: Louis should not be labelled a surrealist. He did not see himself as part of any movement. While some of his work is dreamlike – daydreams or night dreams – he was not reporting literally on his dreams. One thing that is characteristic of much of his work is a strong narrative element even though the story may not be clear to the viewer. There is also a sense of the strangeness of reality, and the wonder of the world.

Public art at Spadina Station, Toronto: “Morning Glory” by Louis de Niverville, photo by TheTrolleyPole, 2017, licensed under Creative Commons

F1: Morning Glory at Spadina Station in Toronto remains one of his most visible works, seen daily by thousands of Torontonians. What does that mural reveal about his artistic vision that perhaps smaller, more intimate works don’t?

PO: Morning Glory is probably the most autobiographical work from Louis’ mature period. The expanse of this piece allowed Louis to tell the story of a little boy confined to his bed daydreaming about what was going on in the world around him. A brilliant story for the subway entrance.

TM: The subway mural tells the essence of his story — the experience of isolation and the longing to go out into the world and enjoy life. As dreamlike as the mural is, it’s probably the closest to an autobiographical work he created.

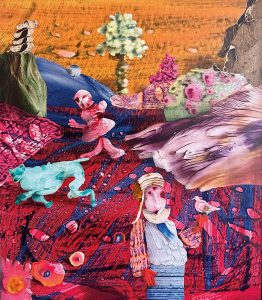

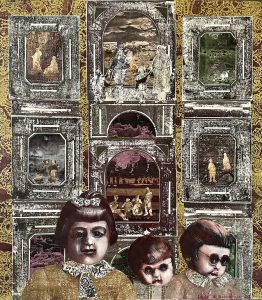

EXTRAVAGAZA 1969, painted collage on board, 61 x 50.8 cm. 24 x 20 inches collection Andree de Niverville,

F1: With over 140 artworks and essays, this is the most comprehensive look at Louis’s work to date. What surprised you most in bringing it together?

PO: Louis’ work always offered the viewer the pleasure of surprise. Many of the works we chose to include were works that I had never seen before, such as Extravaganza and Little River from 1969, which was a thrilling part of the experience for me. I was also reminded over and over again of what a fine craftsman Louis was.

TM: As we researched the book I was reminded again of the incredible variety of subjects, the emotional range and Louis’ interest in exploring the human condition — what it means to be human. His interest in the themes of time, mortality and memory really came into focus. Also his technical virtuosity and interest in exploring various techniques. These characteristics appear consistently throughout his career.

F1: The word “pentimenti” refers to visible traces of earlier painting beneath the surface—an evocative metaphor. Why did you choose this title for the book?

TM: In 1978, Joan Murray, then Director of the Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, organized the large, touring retrospective for Louis. In the catalogue there is an essay in Louis’ voice titled “Pentimenti,” in which he gives his perspective about his work. We used “pentimenti” as a tribute to Joan for her great support for Louis’ career. She also included Louis’ work in the books she wrote about Canadian art. And there is something lovely about saying a word which conveys so much elegiac emotion and a sense of the passage of time.

In a broad sense “pentimenti” means what is revealed with the passage of time. That is the experience we have had as we explored Louis’ 60+ year career, researching books and articles in his archive, visiting the artworks in museums and private collections, and in lengthy discussions among the writers and editors.

Order your copy of Louis de Niverille now.